By Ilene Dube, JerseyArts.com

originally published: 12/19/2024

Kimberly Camp may enjoy playing with dolls, but she knows a thing or two about art.

Having held the top leadership positions at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, the Smithsonian Experimental Gallery, and the African American Museum in Detroit, she was always first and foremost an artist.

Kimberly Camp – Cross River: A Parallel Universe, on view at the Hunterdon Art Museum through Jan. 12, showcases an entire village of her intricately made dolls. Curated by Judith K. Brodsky and Ferris Olin, the exhibition represents 40 years of telling stories in beads, earthenware, stone, textile, faux fur, and metal.

Standing in the first-floor gallery where these dolls are gathered, a visitor can commune with the spirits Camp has summoned.

Kimberly Camp – Cross River: A Parallel Universe

“Camp’s dolls transcend conventional roles, embodying a blend of seriousness and playfulness, spirituality and everyday life,” say the exhibition materials. “They reflect the human condition while challenging preconceived notions about race and identity. Each doll is a testament to the historical and cultural significance of dollmaking, incorporating skills such as sculpting, sewing, beading, and painting.”

Camp’s dolls come into being improvisationally. She starts by making the head and body parts out of clay. When the heads are lined up on her shelf, they speak to Camp, telling her what they want to be. “I never really know what the doll will become until it is finished,” she says.

Once she’s received instruction from the doll, the Camden native constructs armatures and goes through her extensive fabric collection sourced from worldly travels. “Abioudun” wears traditional Malian mud cloth pants. His hat and dashiki are made of Nigerian Asa oke cloth. Olatunji wears a traditional Yoruba outfit made from Ghanaian hand-screened cotton.

The cotton for “Baba” – named for renowned drummer Babatunde Olatunji — was purchased at Marché St. Pierre in Paris. (“Six floors and thousands of textiles from around the world,” notes the artist). The kimono for “Tanuki” is made of antique cloth with a satin obe sash, paper fan, and traditional wooden platform sandals.

The dolls are further festooned with recycled fur and skins to form the bodies, clothing, and adornments. Hand sewing adds personality and attitude to each doll. The final touch is adorning a doll with buttons, feathers, seeds, roots, horns, and beads.

There is a difference between dolls that are toys, meant to be played with, and those created by artists like Camp, points out co-curator Olin. “Artists have a long history of making dolls in the same way that they paint or sculpt,” she says, citing examples by Faith Ringgold and other artists.

Well-crafted dolls, such as those created by Camp, require skills beyond painting or sculpture to include designing and engineering the structural elements, sewing by hand and by machine, beading, making wigs, working with fur, and more. As the daughter of a dental surgeon and a hat maker, Camp learned these skills early in life, spending a lot of time at the library and the local art supply store.

Camp, Kimberly. Brother Black

Their stories come through the names the dolls are given, such as “Soul Searcher,” “Children are our Future,” and “A Bird Told Me.” Some of Camp’s dolls combine features of animals and humans. “Poodle,” for example, has a human head but a body covered in the fur of the aforementioned canine. “Brother Black,” based on the Geechee Gullah tales about B’rer Bear, stands upright like a human but has the head and feet of a bear. “Chirp,” with pink shoes, has the legs of a man but is all bird from its feathered mid-section to its beak. “Alotta” stands tall like an elegant woman at a gallery opening, wearing a black fur cape with strands of necklaces from which dangle exotic pendants, yet her head is that of a bovine. Camp highlights the mythic connections between humans and the animal kingdom, emphasizing shared behaviors and traits.

“The dolls are a reminder that, as part of the animal kingdom, humans and animals share more behaviors and characteristics than we might realize,” says Camp.

“My dolls defy traditional notions of what we assume dolls to be,” says Camp in an artist statement. “They are as serious as they are playful and as spiritual as they are mundane. They reflect the human condition while defining and defying the artificiality of ideas about the social construct of race. And they defy grid-like parameters to imagine a world as multidimensional as only an artist can create.”

Camp, Kimberly. Chirp Feathers

Humans have been creating figures in their own image for thousands of years. “The earliest known examples are paddle dolls from the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2030–1802 BCE), thought to have been used by performers in tribute to the goddess Hathor,” says Camp. “Made of wood, they are decorated with geometric designs and a thick mass of hair made of beads. Dolls in many cultural groups on the African continent are used as spiritual tools for rituals, for honoring ancestors, and for play, teaching, and fertility.

“In Japan,” she continues, “clay figurines called Dogū date back to the Jomon period (14,500–300 BCE.) Today, dolls are central in contemporary Japanese culture and tradition, and are celebrated every year for Hinamatsuri or Girls’ Day, a Shinto religious celebration when dolls are dressed as royalty from the Heian Period and displayed in public.”

With the patterns for the doll clothes she designed on cotton and silk, Camp aims “to help others understand that Blackness is a social construct created to serve the horrific practice of enslavement. Blackness has never defined us; we have always defined ourselves.”

One example is Honey Chile, made of recycled raccoon fur that pokes at multiple racist tropes. The doll’s dress is made of images from the book Little Black Sambo, originally written about a Tamil Indian child but vulgarized to be about a Black American boy. Interspersed within the design on the dress are the words “The Race to Create Race.”

It’s very serious, yes, but while sitting at her work table, Camp has been known to burst into spontaneous laughter. “To me, the dolls are a form of play, even when they tackle awkward cultural assumptions.”

Hunterdon Art Museum is located at 7 Lower Center Street in Clinton, New Jersey.

About the author: Driven by her love of the arts, and how it can make us better human beings, Ilene Dube has written for JerseyArts, Hyperallergic, WHYY Philadelphia, Sculpture Magazine, Princeton Magazine, U.S. 1, Huffington Post, the Princeton Packet, and many others. She has produced short documentaries on the arts of central New Jersey, as well as segments for State of the Arts, and has curated exhibitions at the Trenton City Museum at Ellarslie and Morven Museum in Princeton, among others. Her own artwork has garnered awards in regional exhibitions and her short stories have appeared in dozens of literary journals. A life-long practitioner of plant-based eating, she can be found stocking up on fresh veggies at the West Windsor Farmers Market.

Content provided by

Discover Jersey Arts, a project of the ArtPride New Jersey Foundation and New Jersey State Council on the Arts.

EVENT PREVIEWS

Gallery Bergen presents "OMG" featuring works by Graham Elliott

February 26 to April 10, 2026

Pleiades Gallery presents "Florals for Spring" by Carol Nussbaum

March 17 to April 11, 2026

Part One of RVCC's Annual Student Art Exhibition to Run from February 27th to March 27th

February 27 to April 27, 2026

Gallery on Grant's latest exhibit celebrates Women's History Month

February 26 to June 11, 2026

Neon Nostalgic Presents 80's Music Television at State Theatre

February 21, 2026

UCPAC presents Lez Zeppelin: The Song Remains The Same 50th Anniversary Celebration on February 21st

February 21, 2026

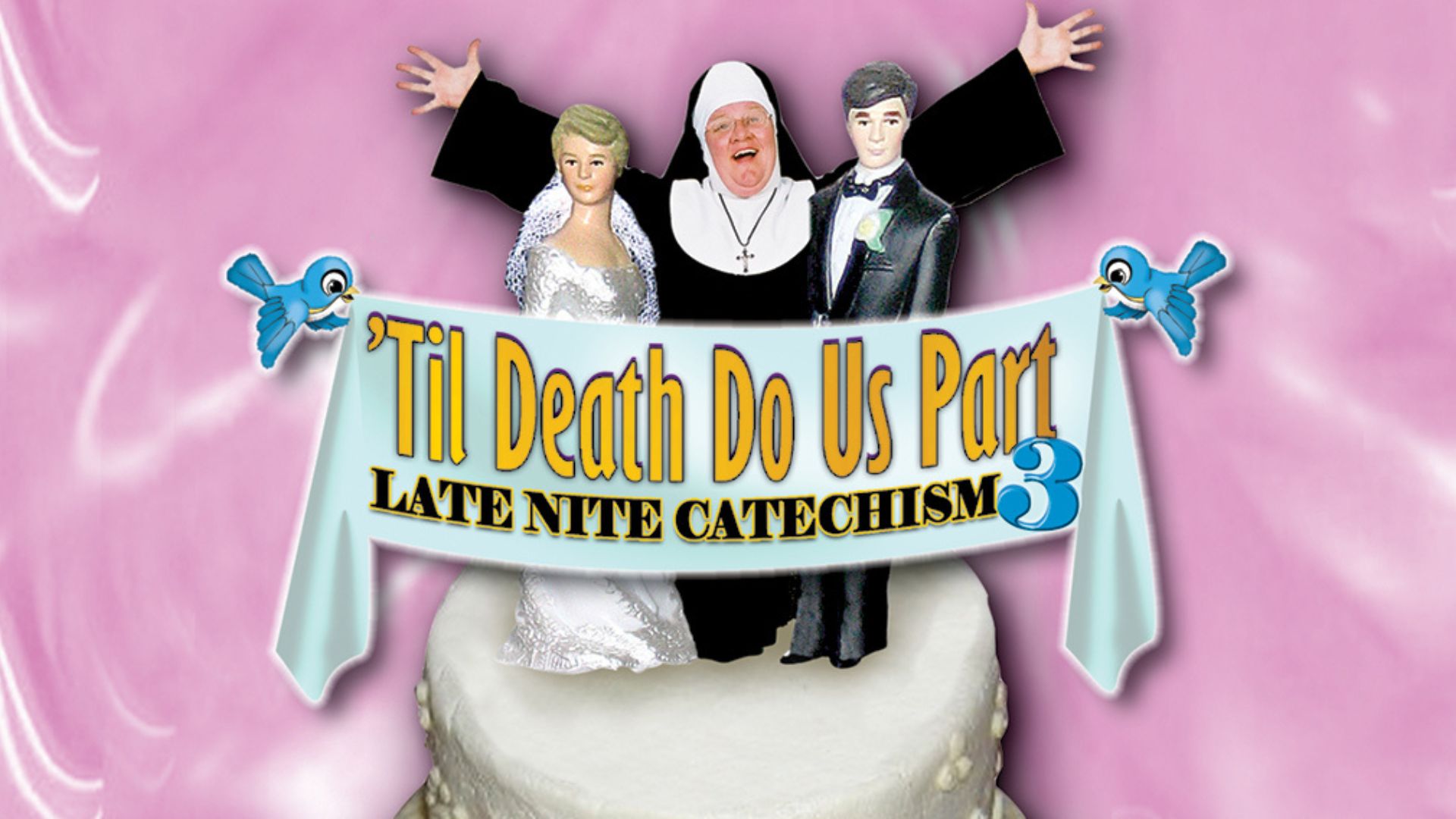

"'Til Death Do Us Part: Late Nite Catechism 3" comes to Grunin Center

February 21, 2026

The Theater Project to present staged reading of three short plays by Rosemary Parrillo

February 21, 2026

Foundation Academies and the Princeton Battlefield Society to launch "Men W/O Shoes" exhibit, telling the untold stories of black Revolutionary War soldiers

February 21, 2026

Harmonium Choral Society's Broadway Cabaret Troupe presents "You Know This Song"

February 21, 2026

FEATURED EVENTS

To narrow results by date range, categories,

or region of New Jersey

click here for our advanced search.